The heat transport into the Nordic Seas from the Atlantic Ocean has been 7 percent higher after 2001 than in the 1990s, according to a study published in Nature Climate Change today.

Jointly referred to as the Arctic Mediterranean, the Arctic Ocean and the Nordic Seas have seen increasing temperatures and declining sea-ice covers in recent years. The observed increase in heat transport can account for most of these changes.

“We see the increase in heat transport as a combination of increased temperature in the Atlantic water and increased volume transport”, lead author Takamasa Tsubouchi writes in an e-mail.

Tsubouchi led the study while working at the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Change and the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen, and now works at the Japan Meteorological Agency.

Substantial change around the turn of the century

“Most significantly, we have quantified the ocean heat transport robustly for the first time, not only the long-term mean, but also its temporal variability”, Takamasa Tsubouchi comments.

“Assembling and adjusting the volume transport estimates of all currents into and out of the Arctic Mediterranean, this study presents, for the first time, time series of ocean heat transport to the Arctic Mediterranean, from 1993 to 2016”, he continues.

The results show a marked increase in the inflow of heat to the Nordic Seas between 1998 and 2002.

“The rise in temperature was not unexpected”, says Takamasa Tsubouchi’s co-author Kjetil Våge, research scientist at the Bjerknes Centre and the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen. “But such a leap in only a few years surprised us.”

The volume budget has to balance

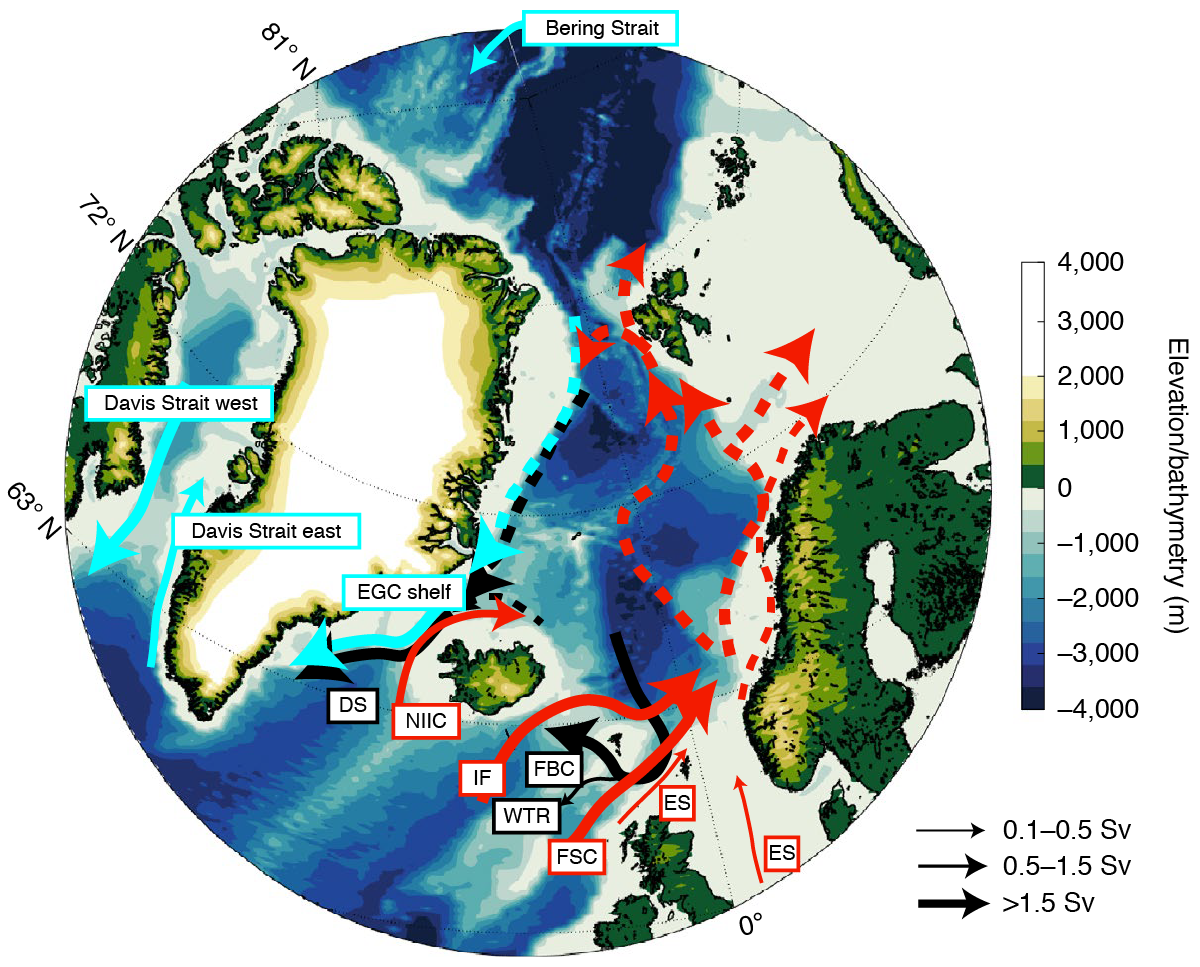

Sea water follows one major route into the Arctic Mediterranean. This route goes through the Nordic Seas, where warm, Atlantic water from the Gulf Stream continues northwards on both sides of Iceland. Cooler water flows northwards along the west coast of Greenland, and from the Pacific Ocean through the Bering Strait, but these currents are weaker and transport less heat.

Two main paths lead back south. Water flows southwards at depth on both sides of Iceland and near the surface on both sides of Greenland. Each of these currents have several branches.

The scientists behind the new study assembled time series for each current to create a complete budget for water flowing into and out of the Arctic Mediterranean. Researchers from NORCE, the Faroe Marine Research Institute, the Scottish Association for Marine Science, and the Icelandic institutions the University of Akureyri and the Marine and Freshwater Research Institute, contributed.

The amount of water going out has to equal that coming in. In periods without observations for one branch, data from other observational periods and the other branches have been used to estimate the missing observations. All measurements have an uncertainty, which can also be quantified. Within these bounds, each current can be adjusted to be in accordance with the total system of currents.

The volume budget must balance.

More heat than before

The heat budget never balances. More heat is brought into the Arctic Mediterranean than what comes out. But in recent years, the surplus has gone up.

Between 1998 and 2002 the amount of heat brought into the Arctic Mediterranean increased abruptly, and it has remained at a higher level since then. The 7 percent increase can account for the recent warming of the Arctic Mediterranean and has likely contributed to the decline in sea ice.

Warmer water and a stronger current contributed equally to the increase, though as the velocity of water is more difficult to measure and more variable in time, the velocity contribution has a higher uncertainty than its temperature contribution. Nevertheless, it is clear that warm inflow into the Nordic Seas has not declined over the monitoring period, it may instead have increased.

No weakening of the overturning circulation observed

Most of the water brought northwards by the Gulf Stream is cooled, sinks and returns southwards at depth. This sinking is of critical importance for maintaining the overturning circulation in the North Atlantic, which the Gulf Stream is one component of.

The sinking occurs in three main regions: the Labrador Sea, the Irminger Sea and the Nordic Seas. Historically, the Labrador Sea was thought to be a main location, but over the last years the focus has shifted to the Nordic Seas.

Climate models indicate that the strength of the overturning in the Atlantic will be reduced by 10–30 percent by the end of this century, if the global warming continues. Whether a weakening has already been observed in the southern part, has been debated.

“We see no sign of a weakening in the north”, says Kjetil Våge. “Our results suggest that the currents into the Nordic Seas are robust. The return current at depth has not changed, either.”

He emphasizes that we still know too little about the link between the southern and the northern part of the overturning circulation to say how this will develop in the future.

References

Tsubouchi, T., Våge, K., Hansen, B. et al. Increased ocean heat transport into the Nordic Seas and Arctic Ocean over the period 1993–2016. Nat. Clim. Chang.(2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00941-3

Østerhus, S. et al. (2019): Arctic Mediterranean exchanges: a consistent volume budget and trends in transports from two decades of observations. Ocean Sci., 15, 379–399, 2019