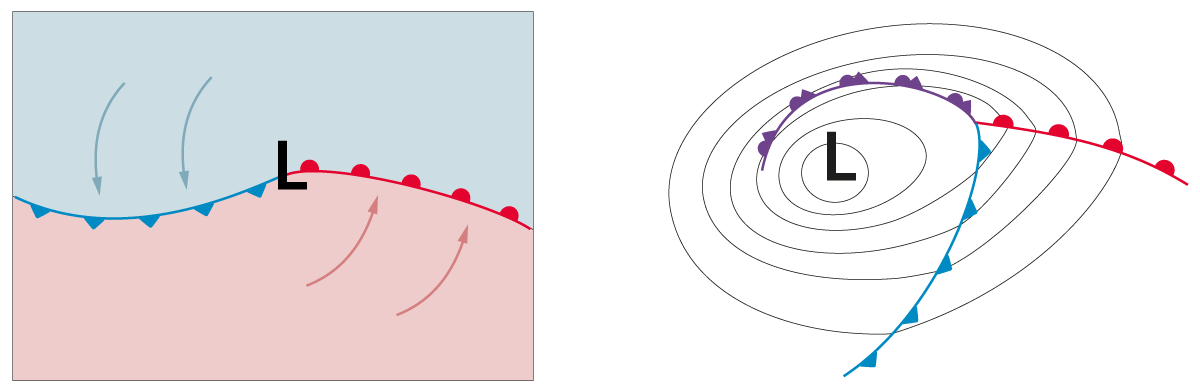

In the decade following World War I, Vilhelm Bjerknes and the Bergen school of meteorology formed the basis for modern weather forecasting. Vilhelm's son, Jacob, was only 21 when he in 1918 described how low pressure systems seem to form on boundaries between warm and cold air.

Working in the aftermath of the war, Bjerknes and his team of young meteorologists chose to call these boundaries fronts. Their concept has become known as the "Norwegian cyclone model".

According to Bjerknes and the Bergen school: first front, then low. The eggs are there, and a low is hatched.

Order revised

Later, examples of the opposite were observed, that lows form without a well-marked weather front, and then generate a front. Almost half a century after Bjerknes and the Bergen school proposed the Norwegian cyclone model, a theory was developed that explained how cyclones can grow in the absence of clear fronts. The low reshapes the temperature field surrounding it in such a way that zones with very strong temperature contrasts emerge.

This – first low, then fronts – became the new standard in meteorology.

Sorted the entire flock

In reality, both these kinds of cyclones exist. But the frequency and distribution of each type has not been known. Extratropical cyclones – lows – that have fronts may have developed along a front, or the fronts may have formed at a later stage of the cyclone’s lifecycle.

“I realized that this chicken-or-egg question had never been analyzed climatologically”, says Sebastian Schemm.

In a new article, Schemm and colleagues show that the answer depends on where you are, and on how you define a front. For this study, they have considered all extratropical cyclones they could identify in the Northern Hemisphere over a period of 35 years.

Their maps are the first to show how common each kind of cyclone is in different regions.

Schemm worked on this while he was a researcher at the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research and the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen, together with colleagues from the ETH in Zürich. The study was published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS) and featured on the cover of the January 2018 edition.

Three types thrive in the cyclone coop

Seated in Bergen, Norway, it was natural that Bjerknes concluded that fronts form before their lows. Schemm and his colleagues found that lows that enter the Norwegian Sea often form on pre-existing fronts in the East Atlantic. The front concept has developed much further since Vilhelm and Jacob Bjerknes’ times, but the order is the same: first front, then low.

Cyclones in the Mediterranean are of the other type. Lows first form, and then later develop fronts.

As for the intense polar lows that strike the coast of Norway, they fly alone. "Polar lows do not have what we would identify as fronts", explains Sebastian Schemm. So, low only, no fronts.

Improving forecasts

Standing on the ground under a passing front, you may feel tempted not to care whether it was formed before or after the low it accompanies. In either case, pouring rain will leave you soaking wet. Looking ahead and over the clouds is still important.

“A better understanding of how weather systems work will in the long run help us to improve weather forecasts”, says Sebastian Schemm. "It is at the front all the exciting weather happens."